Business Case for Nature session with André Hoffmann, Vice-Chairman, Roche Holding; Interim Co-Chair, World Economic Forum, Switzerland; Chavalit Frederick Tsao, Chair, TPC (Tsao Pao Chee) Group, Singapore; David Gelles, Managing Correspondent, New York Times, USA; Kirsten Schuijt, Director-General, WWF International, Switzerland; Rohini Nilekani, Founder and Chairperson, Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, India; at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2026 in Davos-Klosters. Credit: ©2026 World Economic Forum / Mattias Nutt

From unfinished COP30 agendas to ocean governance and forest finance reform, the year ahead points to convergence — and credibility tests — for climate and nature action.

Read more

Related articles for further reading

There is a strange urgency to the start of the year: ambition remains high, but decisive breakthroughs did not fully land, leaving behind unpromised roadmaps, partial finance commitments and lingering questions about implementation.

Governments face unresolved fossil fuel transition and deforestation roadmaps. Financial institutions are confronting mounting evidence that nature loss is macroeconomic risk. Carbon markets are undergoing credibility tests, while a crowded calendar of global summits competes for political attention. All of this is unfolding against a tense geopolitical backdrop that continues to strain multilateral cooperation at precisely the moment when coordination is most needed.

At first glance, these agendas appear to compete for attention. But beneath the noise, they converge on a common denominator: nature. Whether as economic infrastructure, a mitigation pathway, a resilience asset or a source of geopolitical risk, nature sits at the intersection of the year’s most consequential debates. What follows are the key storylines emerging from this convergence — and what they suggest about the direction climate and nature action could take in 2026.

Where next for the Belém Roadmaps?

COP30 closed with measurable progress, but also with conspicuous absences. Governments agreed to triple the global adaptation finance goal and reaffirmed the ambition to mobilize $1.3 trillion annually for climate action. Discussions around structured roadmaps to transition away from fossil fuels and to halt and reverse deforestation gained unusual traction in negotiation rooms.

Those roadmaps are widely seen as the missing piece that could shift implementation from incremental to structural — aligning energy transition and land-use reform in a way that meaningfully bends the emissions curve back toward the Paris Agreement goals. Yet neither roadmap entered the formal decision texts. Updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) were delayed in several cases and, where submitted, often lacked sufficient clarity to place the world on a Paris-aligned pathway.

That gap now defines 2026. This year marks the beginning of the next Global Stocktake cycle, due to conclude in 2028, and the credibility of that process will rest heavily on the strength and clarity of NDCs submitted in this round. Whether fossil fuel transition and deforestation roadmaps are fast-tracked onto formal agendas — and whether adaptation finance commitments are matched with implementation detail — will depend on political will and diplomatic agility in an increasingly complex geopolitical landscape.

In a January letter, COP30 President André Corrêa do Lago reiterated his intention to advance these roadmaps, writing that the climate response “no longer depends on formal authorization” and has become “an unstoppable movement capable of uniting humanity around a common purpose.” The coming negotiations will test how far that sentiment is reflected in formal outcomes.

Nature as Critical Economic Infrastructure

While climate diplomacy wrestles with process, economic institutions are reframing the issue in more structural terms.

Ahead of the World Economic Forum in Davos, the Global Risks Report 2026 ranked extreme weather among the most severe near-term threats to global stability. Over a ten-year horizon, biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse and critical Earth system changes dominated risk projections. Shortly thereafter, the United Kingdom’s Joint Intelligence Committee released a national security assessment concluding that accelerating ecosystem degradation poses direct risks to food systems, energy prices and geopolitical stability. It identified ecosystems such as the Amazon, the Congo Basin and Southeast Asian mangroves as critical to national security interests.

In Davos discussions, executives and financial leaders increasingly described nature-based solutions as economic infrastructure rather than reputational initiatives. Lucy Almond, Chair of Nature4Climate, noted in a recent analysis that “perhaps, for the first time, the world is beginning to ask a different question: not what nature can do for us, but how we can finally invest in what nature uniquely offers.” As implementation accelerates, she argued, nature-based solutions are being recognized as “economic strategies that underpin inclusive growth, resilience, public health and sustainable development.”

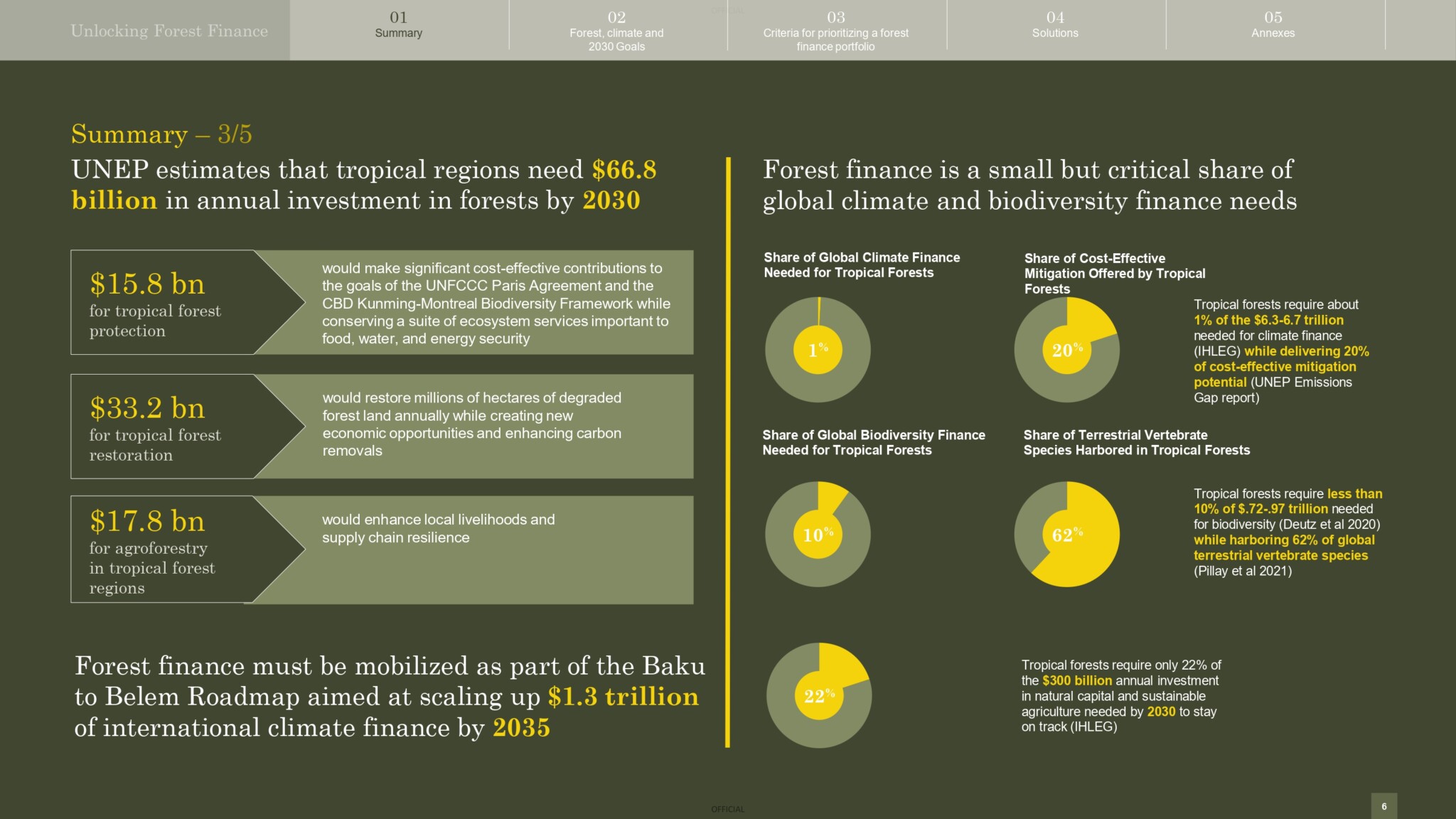

The financial imbalance remains pronounced. UNEP’s State of Finance for Nature 2026 reported that for every US$1 invested in protecting nature, US$30 is spent on activities that degrade it. Nature-negative finance reached US$7.3 trillion, including US$2.4 trillion in harmful public subsidies, compared to US$220 billion directed toward nature-based solutions. Closing that gap would require a significant reallocation of capital, but at less than one percent of global GDP.

These figures help explain why nature should be increasingly discussed within finance ministries and development banks, not solely environmental departments.

Forest Finance and the Carbon Integrity Test

The year also opens with renewed scrutiny of forest finance and carbon markets.

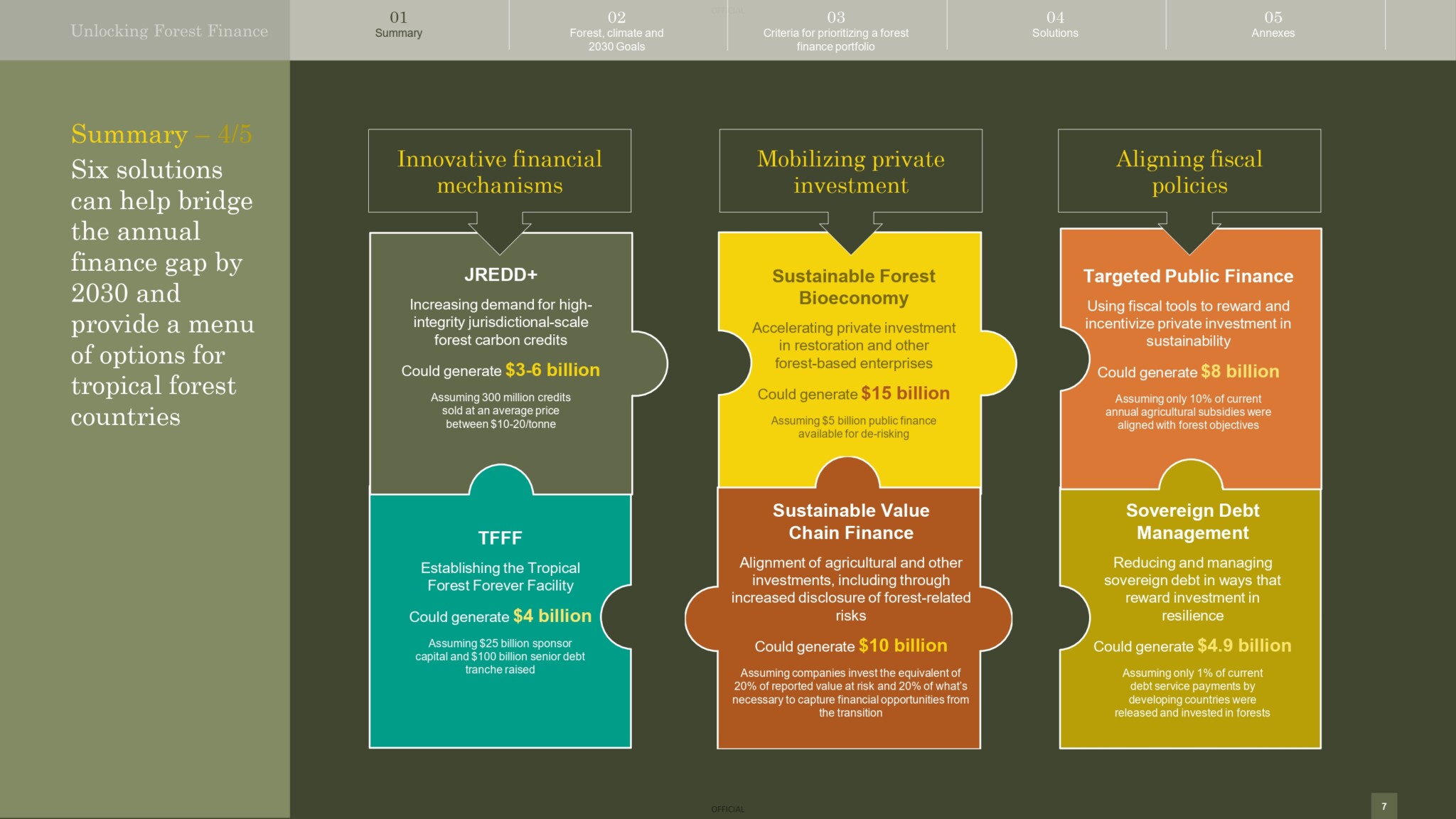

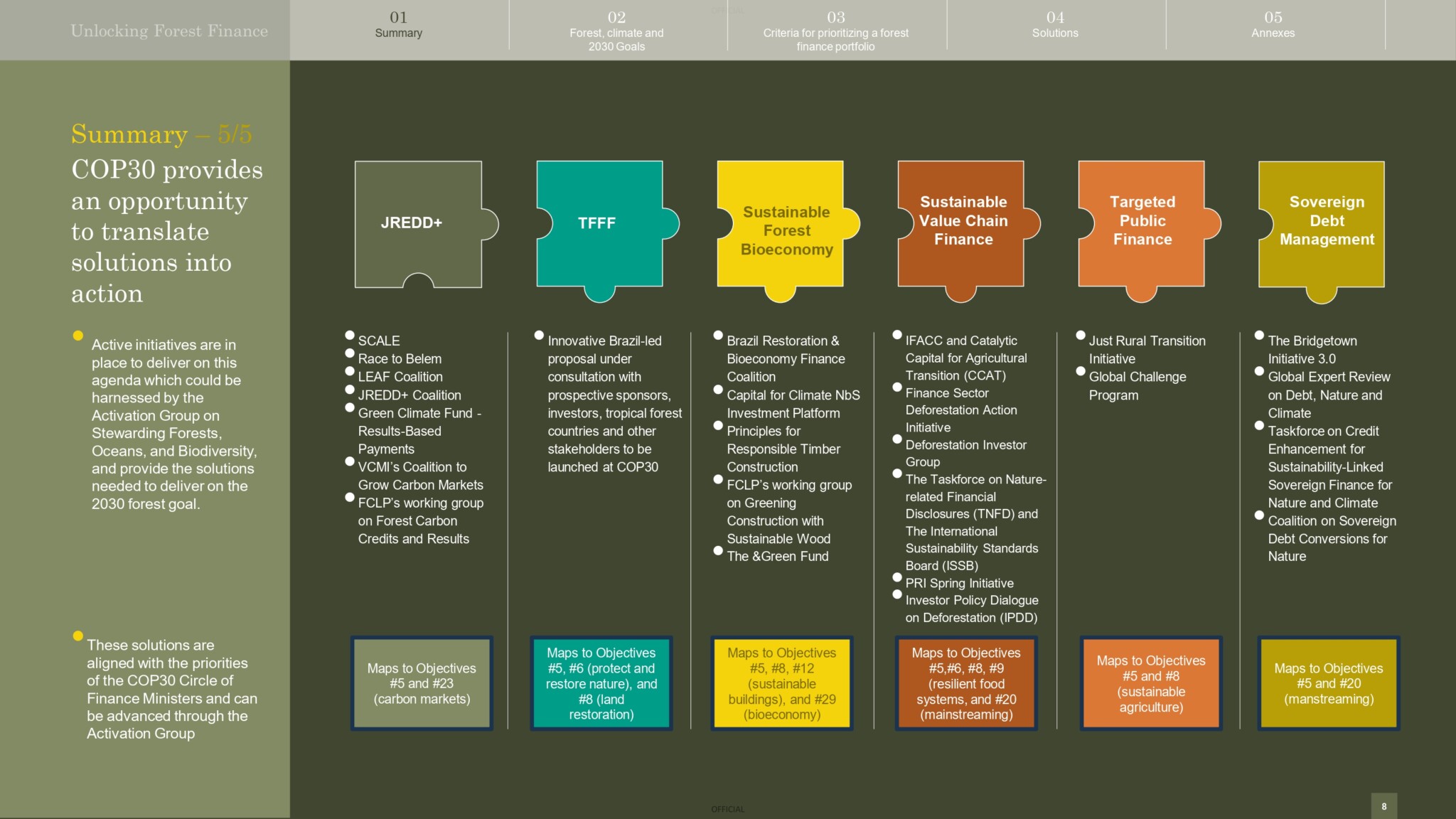

The Tropical Forests Forever Facility, launched at COP30, now enters a phase defined by governance design, capitalization and trust-building. At the same time, the Forest Finance Roadmap introduced during New York Climate Week seeks to redirect commodity finance, scale demand for high-integrity credits and reform fiscal policies linked to land use.

According to Almond, “in the coming years, the world is likely to see the emergence of new blended-finance structures, sovereign forest bonds and corporate alliances organised around forest-investment principles. Crucially, the narrative is shifting from ‘saving trees’ to investing in forest economies.”

Voluntary and compliance carbon markets are undergoing a parallel credibility reset. Standards are tightening, and buyers are demanding greater transparency and impact verification. Whether these reforms restore confidence or prolong hesitation will influence the scale and speed of private capital flows into forest protection and restoration.

A Quadruple COP Year and Ocean Governance

Countries are scheduled to convene this year across the three Rio Conventions — climate (UNFCCC), biodiversity (CBD) and desertification (UNCCD) — a rhythm that, while not unusual, takes on added significance as calls for stronger synergies between the conventions grow more prominent.

What is new is the expected first Conference of the Parties under the High Seas Treaty, focused on areas beyond national jurisdiction. This “Ocean COP” introduces an institutional space dedicated specifically to marine governance at a moment when ocean-based solutions and sustainable marine economies are rising on the climate agenda. COP31, to be held in Türkiye with Australia leading negotiations, is likely to reinforce that prominence.

The convergence of these processes in one year could represent perhaps the strongest opportunity yet to make the case for a more coherent link between ocean and land governance — connecting forest protection, water systems, coastal resilience and marine biodiversity within a single climate stability framework.

The alignment of these processes in a single year creates an opportunity — though not a guarantee — of greater coherence across land, ocean and climate governance. For decades, these conventions have operated in parallel, often addressing interdependent challenges through separate negotiation tracks. The extent to which 2026 advances coordination will shape the durability of outcomes.

The Eroding Window

Nature’s mitigation potential remains substantial but time-sensitive. Nature4Climate scientific advisor Chris Zganjar note: “Protecting, restoring and better managing nature can still deliver almost one-third of the climate mitigation needed to keep 1.5°C within reach. But as time passes and more ecosystems are lost or degraded, the room to maneuver narrows and the options to win this battle diminish”.

Early signals from 2026 point toward convergence: unfinished roadmaps from COP30, heightened economic risk recognition, intensified debates over forest finance integrity and an unprecedented alignment of global environmental summits. The year ahead is unlikely to hinge on a single breakthrough. Instead, its significance may lie in whether these threads begin to reinforce one another — embedding nature more firmly into the structures that shape energy systems, economic planning and global cooperation.

The trajectory is not predetermined. But the architecture of the year suggests that decisions taken now will reverberate well beyond 2026 — shaping the credibility of the next Global Stocktake and the place nature ultimately occupies in climate governance.