Ecosystem services and green infrastructure

The value of the services provided to human society by nature— ranging from cleaner water to reduced flooding to life-sustaining food and medicine—are immense. However, the benefits derived from these “ecosystem services” are systematically undervalued in day- to-day decisions, market prices and economic accounting. It is vital for global policy makers to account for the economic value of nature when making decisions about the shape of our post-COVID economic recovery.

Headline statistics

- The most comprehensive global estimate suggests that ecosystem services provide benefits of $125- 140 trillion per year i.e. more than one-and-a-half times the size of global GDP.

- If today’s mangroves were lost, 18 million more people would be flooded every year (a 39% increase) and annual damages to property would increase by 16% ($82 billion).

- Leading forest specialists and economists estimate that conserved and sustainably managed forests generate more than $6,000 per hectare per year in aggregate value, with values varying between forests and coming mainly from non-remunerated ecosystem services.

Ecosystem services

- The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate says that for forests and natural ecosystems, the greatest economic value generated is not from products but from ecosystem services, most of which are not currently traded in markets. The benefits derived from biodiversity and ecosystem services are considerable, but are systematically undervalued or unvalued in day-to-day decisions, market prices and economic accounting. Conventional accounting approaches and measures of economic performance (such as GDP) provide only a limited picture of an economy’s health, and generally overlook the costs of ecosystem degradation. Thousands of valuation studies are available at the local, regional and global scales, providing estimates of the benefits delivered by biodiversity and ecosystem services (e.g. pollination, climate regulation and water purification).[1]

- The OECD says that although economic valuation of biodiversity continues to face some methodological limitations, it remains a useful and necessary tool for integrating biodiversity values into policy making, as they are otherwise effectively priced at zero. The decisions of ministries responsible for national development strategies and budget allocations, for example, are informed predominantly by interests such as economic growth, competitiveness, food security, and other issues that are politically weightier or perceived to be more pressing. Putting a monetary value on ecosystem services can help convey their importance, and ultimately lead to more efficient, cost-effective and equitable decisions.[2]

- Estimates of the value of ecosystem services provided by forests are typically very large, and mostly need to be derived from models and related calculations, as opposed to being observed in a marketplace.[3] The most comprehensive global estimate suggests that ecosystem services provide benefits of $125-140 trillion per year i.e. more than one-and-a-half times the size of global GDP.[4] A 2011 update of a landmark 1997 estimated that forests alone in 2011 provided ecosystem services worth $16.2 trillion in 2011 prices.[5]

- Leading forest specialists and economists estimate that conserved and sustainably managed forests generate more than $6,000 per hectare per year in aggregate value, with values varying between forests and coming mainly from non-remunerated ecosystem services.[6]

- The World Bank argues that widespread loss of forestland can have significant, potentially irreversible effects that are not fully accounted for in the monetary value of forests included in the wealth accounts—for example, adverse impacts on water regulation, loss of protection from natural hazards, and reduced biodiversity and carbon storage. The conversion of forestland to other uses may be far worse than the monetary accounts indicate because the accounts are largely based on market prices that do not fully reflect the loss of non-market ecosystem services and externalities.[7]

Green infrastructure

- There is also increasing recognition that ‘green infrastructure’—forests, wetlands, and mangroves for example— can perform better and at lower cost than ‘grey infrastructure’ for services such as flood management, water purification and storage and irrigation. The potential here is huge: the OECD estimates global financing needs for water supply infrastructure at $6.3 trillion by 2030.[8]

- Investments in nature-based infrastructure have proven, multiple benefits; for example, reforestation projects in upper catchments sequester carbon, support nature, reduce flood risk, improve soil quality and improve local water supplies.[9] Other examples include coastal habitat restoration1[10] to enhance protection from floods and storms whilst increasing the quality of local fisheries; wetlands systems that provide sustainable urban drainage; and peatland restoration programmes that reduce carbon emissions, restore biodiversity and reduce the speed of run-off to local rivers.[11] [12]

- The worsening impacts of climate change could force over 140 million people to move within their countries, due to a series of growing problems that could be addressed by restoring degraded lands into productive and healthy ecosystems.[13]

- TNC has found that in the past 30 years, the amount of the world’s GDP annually exposed to tropical cyclones has increased by more than $1.5 trillion. Insurers alone have paid out more than $300 billion for coastal damages from storms in the past 10 years.[14]

- The FAO argues that forests and mangroves play a key role in adaptation. They reduce economic losses and overall risk from floods and droughts, which caused $1.5 trillion in damage worldwide between 2003 and 2013, which is expected to worsen with climate change.[15]

- If today’s mangroves were lost, 18 million more people would be flooded every year (a 39% increase) and annual damages to property would increase by 16% ($82 billion).[16] 32% more people would be flooded under 1 in 10- year events, and 16% more people would be flooded under 1 in 100-year events.[17]

Asia

China

In the Upper Yangtze River Basin in western China, flood mitigation provided by forests saves an average of $1 billion annually from avoided storm and flood damage.[18]

In China, mangroves protect 800,000 people from flooding and $19 billion of property from flood damage.[19]

South Korea

Over the past few decades, South Korea has restored more than 6 million hectares of degraded, sloping lands. The resulting erosion control and prevention of landslides have been valued at $11.23 billion, and $3.95 billion respectively.[20]

Philippines

Restoring mangroves to their geographic coverage of the 1950s in the Philippines would deliver more than $450 million per year in additional flood protection benefits.[21]

Also, in the Philippines, mangroves reduce annual flooding to people by 24%, providing direct benefits to more than 600,000 people every year, many of whom currently live in poverty. Mangroves reduce annual damage to residential and industrial property by 28%, providing more than $1 billion in annual averted damages. They also reduce flooding from 766 km of roads annually. One hectare of mangroves in the Philippines provides on average more than $3,200/year of direct flood reduction benefits. For catastrophic events, such as the 1-in-50-year storm, mangroves avert more than $1.7 billion in property damages. Based on the Philippines’s current population, the mangroves lost between 1950 and 2010 have resulted in increases in flooding to more than 267,000 people every year. Restoring these mangroves would bring more than $450 million/year in flood protection benefits.[22]

India

In India, mangroves protect 3.3 million people from flooding and $9 billion of property from flood damage.[23]

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, mangroves protect 1.3 million people from flooding and $2 billion of property from flood damage.[24]

In the Upper Yangtze River Basin in western China, flood mitigation provided by forests saves an average of $1 billion annually from avoided storm and flood damage.[18]

In China, mangroves protect 800,000 people from flooding and $19 billion of property from flood damage.[19]

South Korea

Over the past few decades, South Korea has restored more than 6 million hectares of degraded, sloping lands. The resulting erosion control and prevention of landslides have been valued at $11.23 billion, and $3.95 billion respectively.[20]

Philippines

Restoring mangroves to their geographic coverage of the 1950s in the Philippines would deliver more than $450 million per year in additional flood protection benefits.[21]

Also, in the Philippines, mangroves reduce annual flooding to people by 24%, providing direct benefits to more than 600,000 people every year, many of whom currently live in poverty. Mangroves reduce annual damage to residential and industrial property by 28%, providing more than $1 billion in annual averted damages. They also reduce flooding from 766 km of roads annually. One hectare of mangroves in the Philippines provides on average more than $3,200/year of direct flood reduction benefits. For catastrophic events, such as the 1-in-50-year storm, mangroves avert more than $1.7 billion in property damages. Based on the Philippines’s current population, the mangroves lost between 1950 and 2010 have resulted in increases in flooding to more than 267,000 people every year. Restoring these mangroves would bring more than $450 million/year in flood protection benefits.[22]

India

In India, mangroves protect 3.3 million people from flooding and $9 billion of property from flood damage.[23]

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, mangroves protect 1.3 million people from flooding and $2 billion of property from flood damage.[24]

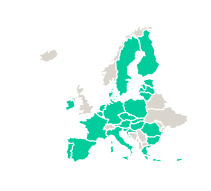

Europe

Ecosystem services provided by the EU’s terrestrial Natura 2000 network and related socio-economic benefits amount to €200 to 300 billion a year.[25]

Protecting coastal wetlands in the EU could save the insurance industry around €50 billion annually through reducing flood damage losses.[26]

Switzerland

In Switzerland, the benefits of protected forests are estimated at $2-3.5 billion per year due to avoided costs of avalanches, landslides, rock falls and flooding. [27]

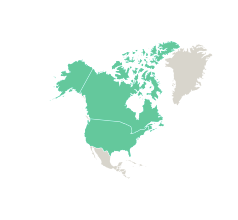

North America

United States

Forests supply drinking water for 180 million Americans in 68,000 communities, making forests the largest source of drinking water in the United States. Forests managed by the US Forest Service provide water to 66 million people in 3,400 communities across 33 states.[28] In 2000, the United States Department of Agriculture estimated the value of water from Forest Service lands at least $3.7 billion per year.[29]

Studies across the US show the return on investment resulting from both public and private conservation dollars. The Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) estimated that for every $1 invested in land conservation, $4 is returned in natural goods and services such as drinking water protection and flood control.[30]

A US study found that drinking water treatment costs decrease as the amount of forest cover in the relevant watershed increases. The share of forest cover in a US watershed accounts for about 50-55% of the variation in water treatment costs.[31]

An analysis of options for improving water quality in Portland found that green infrastructure would be 51-76% cheaper ($68-72 million cheaper) than water-filtration plant upgrades and would bring ancillary benefits (i.e. salmon habitat and carbon sequestration) estimated conservatively at $72-125 million.[32]

A cost-benefit analysis conducted for Philadelphia estimated the net present value of low-impact “green” infrastructure for storm-water control (e.g. tree planting, permeable pavement, green roofs) at $1.94-4.45 billion over a 40-year period. The net benefits for the grey-infrastructure alternative (e.g. storage tunnels) were much lower at $0.06-0.14 billion.[32]

As of 2008, the total estimate of water infrastructure needs for the US included $63.6 billion for combined sewer overflow control and $42.3 billion for stormwater management. Green infrastructure projects are a cost-effective way to address this need.[34]

Spending $100 million on green infrastructure in Lynchburg, Virginia would create about 1,400 jobs and for every dollar invested, an estimated $3.15 of economic activity is generated.[35]

In the US, studies show that conserving and restoring wetlands, salt marshes, and mangroves is one of the most cost-effective ways to protect coastal areas. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that major floods have caused an average of $4.6 billion in damage per event since 1980.[36]

Scientists estimate that US coastal wetlands provide $23.2 billion in storm protection services each year.[37]

An assessment of the value of coastal wetlands in the North-eastern US found that wetlands prevented $625 million of flood damage from Superstorm Sandy in 2012 and lowered flood damage by 11% on average. A more localised study in the region estimated that properties located behind marshes in Barnegat Bay, New Jersey, suffered 16% less annual flood damage than properties that had lost their marshes.[38] Protecting coastal wetlands could save the insurance industry $52 billion a year through reduced losses from storm and flood damage.[39]

A study in PLoS One found that nature-based solutions, such as wetland and oyster reef restoration, could prevent up to $50 billion in losses from projected flooding increases along Florida’s coast over the next decade. Such natural solutions also had a projected benefit-to-cost ratio of 3.5.[40]

In Massachusetts, the Department of Fish and Game, Division of Ecological Restoration (DER) has found that “for every $1 million spent, the average economic output of DER projects generates a 75% return on investment and creates or maintains 12.5 full-time- equivalent jobs.” Restoration projects generate total economic outputs equal to or greater than other types of capital projects such as road and bridge construction and repair, replacement of water infrastructure, etc.[41]

During Hurricane Irma, mangroves averted $1.5 billion in surge-related flood damages to properties, representing a 25% saving in counties with mangroves. Every hectare of mangroves with properties behind them provided, on average, $7,500 in risk reduction benefits during Hurricane Irma.[42]

Coastal wetlands in the north-eastern US prevented more than US $625 million in direct property damage during Hurricane Sandy, reducing damage by an average of 22% in over half the affected areas.[43]

The total economic value of coral reef services for the US—including fisheries, tourism, and coastal protection—is over $3.4 billion each year.[44]

Canada

Forests in Canada store over 200 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide and are home to more than one million First Nations indigenous people. A carbon management programme in Manitoba and Alberta aims to capture between 400,000 and 800,000 tonnes of carbon annually, generating economic benefits for indigenous communities. [45]

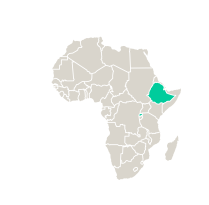

Africa

Ethiopia and Rwanda

Restoration in the Tigray region of Ethiopia and better land husbandry in Rwanda has enhanced farmers’ resilience, water availability, and livelihoods in areas previously subject to poverty and desertification.[46]

Latin America and the Caribbean

Colombia

In Colombia, maintaining the forested lands of the Colombian Amazon held by indigenous communities could yield as much as $123 billion to $277 billion in total ecosystem benefits over a 20-year period.[47]

Mexico

In Mexico, mangroves protect 300,000 people from flooding and $9 billion of property from flood damage.[48]

Browse the rest of the campaign

Resources

[1] The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, The New Climate Economy: Better Growth Better Climate(2014)

[2] OECD, Biodiversity: Finance and the Economic and Business Case for Action, report prepared for the G7 Environment Ministers’ Meeting (2019)

[3] OECD, Biodiversity: Finance and the Economic and Business Case for Action, report prepared for the G7 Environment Ministers’ Meeting (2019)

[4] Costanza, et al, Changes in the global value of ecosystem services (2014)

[5] Costanza, et al, Changes in the global value of ecosystem services (2014)

[6] Costanza, et al, Changes in the global value of ecosystem services (2014)

[7] World Bank, The Changing Wealth of Nations 2018: Building a Sustainable Future (2018)

[8] OECD, Financing Climate Futures; Rethinking Infrastructure (2018)

[9] Bonn Challenge, Restoration Benefits

[10] Nature4Climate, Coastal Wetland Restoration

[11] Ossa-Moreno et al, Economic analysis of wider benefits to facilitate SuDS uptake in London, UK (2017)

[12] IUCN, New Report highlights multiple benefits of peatland restoration around the world (2014)

[13] World Bank, Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration (2018)

[14] The Nature Conservancy, The Global Value of Mangroves for Risk Reduction (2018)

[15] FAO, The Impact of Disasters on Agriculture and Food Security (2015)

[16] World Economic Forum, 2020, Nature Risk Rising (2020

[17] World Economic Forum, 2020, Nature Risk Rising (2020

[18] The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, The Sustainable Infrastructure Imperative (2016)

[19] The Nature Conservancy, The Global Value of Mangroves for Risk Reduction (2018)

[20] The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, Unlocking the Inclusive Growth of the 21st Century (2018)

[21] The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, Unlocking the Inclusive Growth of the 21st Century (2018)

[22] The Nature Conservancy, The Global Value of Mangroves for Risk Reduction (2018)

[23] The Nature Conservancy, The Global Value of Mangroves for Risk Reduction (2018)

[24] The Nature Conservancy, The Global Value of Mangroves for Risk Reduction (2018)

[25] Institute for European Environmental Policy, Natura 2000 & Jobs (2017)

[26] European Commission, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030

[28] USDA, Water Facts

[29] USDA, Water & The Forest Service (2000)

[30] The Trust for Public Land, Return on the Investment from the Land & Water Conservation Fund

[31] Fiquepron et al, Land use impact on water quality: Valuing forest services in terms of the water supply sector (2013)

[32] OECD, Biodiversity: Finance and the Economic and Business Case for Action, report prepared for the G7 Environment Ministers’ Meeting (2019)

[33] OECD, Biodiversity: Finance and the Economic and Business Case for Action, report prepared for the G7 Environment Ministers’ Meeting (2019)

[34] EPA, Benefits of Green Infrastructure (2008)

[35] University of Maryland Environmental Finance Center, Stormwater Financing Economic Impact Assessment: Anne Arundel County, MD, Baltimore, MD, and Lynchburg, VA (2013)

[36] NOAA, Calculating the Cost of Weather and Climate Disasters (2020)

[37] Narayan et al, The Effectiveness, Costs and Coastal Protection Benefits of Natural and Nature-Based Defenses(2016)

[38] Narayan et al, The value of coastal wetlands for flood damage reduction in the Northeastern USA (2017)

[39] World Economic Forum, Nature Risk Rising (2020)

[40] Reguero et al, Comparing the cost effectiveness of nature-based and coastal adaptation: A case study from the Gulf Coast of the United States (2018)

[41] DFG, Economic Benefits from Aquatic Ecological Restoration Projects in Massachusetts: Summary of Three Phases of Investigation (2015)

[42] Narayan et al, Valuing the Flood Risk Reduction Benefits of Florida’s Mangroves (2018)

[43] Narayan et al, The value of coastal wetlands for flood damage reduction in the Northeastern USA (2017)

[44] NOAA, Coral Reef Conservation Program, Total Economic Value of US Coral Reefs (2013)

[45] The Nature Conservancy, Lands of Opportunity (2017)

[46] The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, Unlocking the Inclusive Growth of the 21st Century (2018)

[47] Veit & Ding, Protecting Indigenous Land Rights Makes Good Economic Sense (2016)

[48] The Nature Conservancy, The Global Value of Mangroves for Risk Reduction (2018)