Tourism

The travel and tourism industries represent 10% of global GDP and support one-tenth of our global workforce; of that, 3.9% is for ‘wildlife tourism’, which equals almost 22 million jobs—and these industries have been hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 crisis. Nature plays a key role in sustaining both the tourism economy and conservation work in many countries around the world. By investing in protecting and enhancing nature, we can help tourism-based economies recover, while creating millions of new ecological restoration jobs.

Headline statistics

- While the travel and tourism sectors account for 10.4% of global GDP as a whole, wildlife tourism represents 3.9% of this figure, or $343.6 billion—a figure equivalent to the entire GDP of South Africa or Hong Kong.

- Globally, 21.8 million jobs or 6.8% of total jobs sustained by global travel and tourism in 2018 can be attributed to wildlife.

- People enjoy forests for hiking, camping, hunting, bird-watching, and other forms of recreation. Tourism to protected areas, for example, generates an estimated $600 billion annually, compared to (est.) $10 billion spent on protecting these sites, providing a 60:1 return on investment.

Nature-based solutions

- While the travel and tourism sectors account for 10.4% of global GDP as a whole, wildlife tourism represents 3.9% of this figure, or $343.6 billion; a figure equivalent to the entire GDP of South Africa or Hong Kong. Globally, 21.8 million jobs or 6.8% of total jobs sustained by global travel and tourism in 2018 can be attributed to wildlife.[1]

- People enjoy forests for hiking, camping, hunting, bird-watching, and other forms of recreation. Tourism to protected areas, for example, generates an estimated $600 billion annually, compared to an estimated $10 billion spent on protecting these sites. That equals a 60:1 return on investment.[2]

Coral reefs and mangroves

- Coral reefs alone generate $36 billion per year for the global tourism industry.[3]

- The most popular mangrove sites attract hundreds of thousands of visitors per year and may generate millions of dollars in visitor expenditure.[4] Globally, mangroves support a multi-billion-dollar recreation and tourism industry.[5]

- Ocean tourism is valued at $390 billion globally and is the source of millions of jobs, in many developing nations.[6]

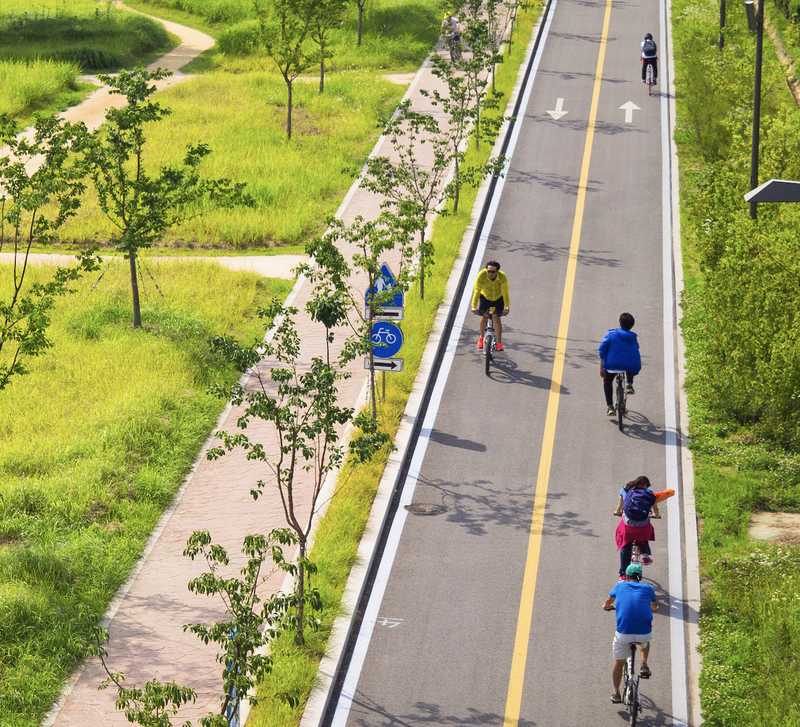

Asia

In the Asia-Pacific region more than 10 million jobs rely on wildlife tourism.[7]

China

In China, forest-based recreation and tourism in forest parks generates about $3.3 billion in entry fees alone.[8]

Vietnam

A 2013 study estimated the value of mangrove tourism in Vietnam to be over $100 million per year.[9]

Europe

In the EU, 1.2–2.2 billion visitor days to Natura 2000 sites generate recreational benefits worth €5-9 billion annually.[10]

The tourism sector employs 12 million people in Europe. Of these, 3.1 million have links to protected areas such as Natura 2000.[11]

North America

United States

It is estimated that the Great American Outdoors Act, which passed the Senate in June 2020, will create as many as 100,000 new jobs.[12]

In the US, recreation and tourism in national forests alone contribute $2.5-3 billion per year to national GDP.[13]

Wildlife tourism supports 500,000 jobs.[14]

Local public park and recreation agencies generate $154 billion in economic activity and support 1.1 million jobs every year.[15]

National parks generate $21 billion in visitor spending and support 340,500 jobs.[16]

National Heritage Areas are estimated to generate $12.9 billion annually, support 148,000 jobs, and provide $1.2 billion in federal taxes.[17]

Proximity to national parks and national monuments brought clear economic benefits; national parks generated $35.8 billion for gateway communities in 2017, and employment and per-capita income improved in regions adjacent to national monuments.[18]

Almost 2.4 million people are employed in ocean-based tourism in the recreation sector, earning approximately $58.7 billion in annual wages. The industry grew by 73,000 jobs (6.3% growth) between 2015-2016, three times faster than the US economy as a whole.[19]

In 2016, the US Fish and Wildlife Service reported 103.7 million Americans participated in wildlife-related recreation, generating $156.9 billion.[20]

Outdoor Industry Association (OIA) has conducted research and analysis for each state to determine the contribution of outdoor recreation.

Canada

In 2019 Canada’s national parks and historic sites saw 25.1 million visitors. Canada’s population that same year was 39.6 million people.[21]

The Province of British Columbia stated in its 2020 Emerging Economy Task Force Report that “B.C.’s natural environment, cultural experiences, and its reputation of being safe, diverse and wild are competitive advantages attractive to tourists”. In 2017, BC tourism revenue was CAD$18.4 billion, an 8.4% increase from the previous year contributing over CAD$9 billion (3.6%) to provincial GDP and employing 138,000 people in over 19,000 businesses.[22]

In 2009 Canada’s federal, provincial and territorial parks contributed CAD$4.6 billion to GDP, representing 2.0% of provincial/territorial GDP and 2.5% of federal GDP. Parks contributed CAD$2.9 billion in labour income and employed 64,050 full time equivalents.[23]

In 2012, a national survey concluded Canadian adults made an estimated CAD$41.3 billion in expenditures for nature-based activities during the year, with the greatest amount dedicated to non-motorized, non-consumptive activities. Expenditures included: nature-based leisure CAD$6.2 billion; non-commercial fishing $2.2 billion; and non-commercial hunting and trapping CAD$1.8 billion.[24]

Indigenous Peoples’ territories represent much of the natural lands and waters in Canada and tourism plays a critical role in local economies. In 2019 Indigenous tourism was a 1.9 billion industry in direct GDP, with 20% annual growth rate, 40,000 employees and 19,000 businesses across Canada.[25]

Africa

In Africa, it is estimated that 80% of tourism trips are ‘nature-based’.[26] The World Travel and Tourism Council estimates that 8.8 million people are employed in the nature-based tourism industry, worth $29 billion in 2018.[27]

Kenya

In Kenya, the tourism sector, which is almost exclusively nature-based tourism focused on wildlife, earns an average of $1 billion annually.[28] International tourism receipts contribute 2% to GDP and contributes significantly to employment.[29]

Namibia

In Namibia, nature-based tourism based in community conservation contributed $488 million in 2018 to net national income and created 5,147 jobs from 1990 to 2016. Namibia’s GDP in 2018 was $14.2 billion.[30]

Uganda

In Uganda, gorilla nature-based tourism contributes $34 million to the local economy.[31]

Botswana

In Botswana, nature-based tourism is the second most important industry: 3% of GDP is from international tourism receipts and 76,000 jobs—7.6% of total employment (combined indirect and direct) from tourism overall.[32]

Tanzania

In Tanzania, nature-based tourism employs 467,000 people employed directly, and more than 1 million indirectly, constituting 12% of total employment.[33]

Latin America and the Caribbean

Costa Rica

In Costa Rica, forests have underpinned the country’s tourism industry growth, which at 7.4% in 2011 was the strongest in the Americas, with ecotourists representing more than half of the 2 million international visitors to the country each year.[34]

Mexico

In Mexico’s Gulf of California and Baja California Peninsula (GCBP), marine ecosystems support tourism activities in many communities—each year nature-based marine tourism in the GCBP results in 896,000 visits, $518 million in expenditures and at least 3,575 direct jobs from formal operations.[35]

Resources

[1] World Travel and Tourism Council, The Economic Impact of Global Wildlife Tourism (2019

[2] Balmford et al., Walk on the Wild Side: Estimating the Global Magnitude of Visits to Protected Areas (2015)

[3] OECD, Biodiversity: Finance and the Economic and Business Case for Action, report prepared for the G7 Environment Ministers’ Meeting (2019)

[4] Spalding & Parrett, Global patterns in mangrove recreation and tourism (2019)

[5] Spalding & Parrett, Global patterns in mangrove recreation and tourism (2019)

[6] OECD, The Ocean Economy in 2030 (2016)

[7] World Travel and Tourism Council, The Economic Impact of Global Wildlife Tourism (2019

[8] The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, The New Climate Economy: Better Growth Better Climate(2014)

[9] Kuenzer & Tuan, Assessing the ecosystem services value of can Gio mangrove Biosphere Reserve: combining earth-observation- and household- survey-based analyses (2013)

[10] Institute for European Environmental Policy, Natura 2000 & Jobs (2017)

[11] European Commission, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030

[12] Politico, Senate passes major conservation package (2020)

[13] The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, The New Climate Economy: Better Growth Better Climate(2014

[14] World Travel and Tourism Council, The Economic Impact of Global Wildlife Tourism (2019

[15] National Recreation and Park Association, The Economic Impact of Local Parks (2020)

[16] National Park Service, Visitor Spending Effects – Economic Contributions of National Park Visitor Spending (2020)

[17] TrippUmbach, The Economic Impact of National Heritage Areas (2013)

[18] National Park Service, Zinke Announces $35.8 Billion Added to U.S. Economy in 2017 due to National Park Visitation (2018)

[19] NOAA, Office for Coastal Management. Fast Facts: Tourism and Recreation

[20] US Fish and Wildlife Service, Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife Associated Recreation: 2016 National Survey (2016)

[21] Parks Canada (2018-19)

[22] British Columbia Emerging Economy Task Force (2020)

[23] The Economic Impact of Canada’s National, Provincial & Territorial Parks (2009)

[24] Canadian Nature Survey (2012)

[25] Forbes, The Impact of shutdown on indigenous tourism (2020)

[26] Planet Tracker, Building Back Better: a Marshall Plan for Natural Capital: Reversing the decline in Sub-Saharan African GDP in Nature-Based Tourism Sector from COVID-19 (2020)

[27] Planet Tracker, Rebuilding Global Nature-Based Tourism

[28] Planet Tracker, Rebuilding Global Nature-Based Tourism

[29] Planet Tracker, Building Back Better: a Marshall Plan for Natural Capital: Reversing the decline in Sub-Saharan African GDP in Nature-Based Tourism Sector from COVID-19 (2020)

[30] World Bank, Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism (2018)

[31] World Bank, Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism (2018)

[32] Planet Tracker, Building Back Better: a Marshall Plan for Natural Capital: Reversing the decline in Sub-Saharan African GDP in Nature-Based Tourism Sector from COVID-19 (2020)

[33] Planet Tracker, Building Back Better: a Marshall Plan for Natural Capital: Reversing the decline in Sub-Saharan African GDP in Nature-Based Tourism Sector from COVID-19 (2020)

[34] The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, Unlocking the Inclusive Growth of the 21st Century (2018)

[35] Cisneros-Montemayor et al, Nature-based marine tourism in the Gulf of California and Baja California Peninsula: Economic benefits and key species (2019)